This piece is a companion to the video below:

A year and a half ago I contacted the Academy of Ideas to collaborate with them in making one of their videos. I wanted to see if I could put into practice the principles behind their popular philosophical slash self-help videos in developing a creative project from scratch.

There was a staccato email thread over three months as we mulled over the topic and schedule. Then, all at once, they sent me a script, mp3 track and well wishes.

The rest was up to me: the visuals, the animation, the direction.

The script had a central idea: according to Leonardo da Vinci, a good life comes about from continually working at projects we think are worthwhile.

Easy! I’d found a worthwhile project I was happy to spend some time on so I was ready to live the good life, thank you very much.

Putting Leo’s ethos into practice was, of course, way harder than reading about it. But his principles guided this project in ways I couldn’t have foreseen, elevating the result to something I couldn’t have imagined at the outset. Here are the details.

Vain pursuits

This line in the video set the tone for how I wanted to work on the project:

“We may be one of the few who scales the ladders of social success to great heights, but if this has come at the cost of years or decades consumed in a job we dread…it will be difficult not to feel we have wasted our life in vain pursuits.”

As a commercial motion designer by trade, my job is to satisfy clients. I don’t dread it, exactly, but much of commercial work does feel like engaging in “vain pursuits”: making things move across the screen at a faster and faster clip as screens and social media break our attention into little pieces. (More ranting here.)

So I decided this video I would make with the Academy of Ideas wouldn’t be so fragmented and busy and quick like so much of the unsatisfying work I was doing, but its opposite: one coherent picture after another, revealed gradually in time.

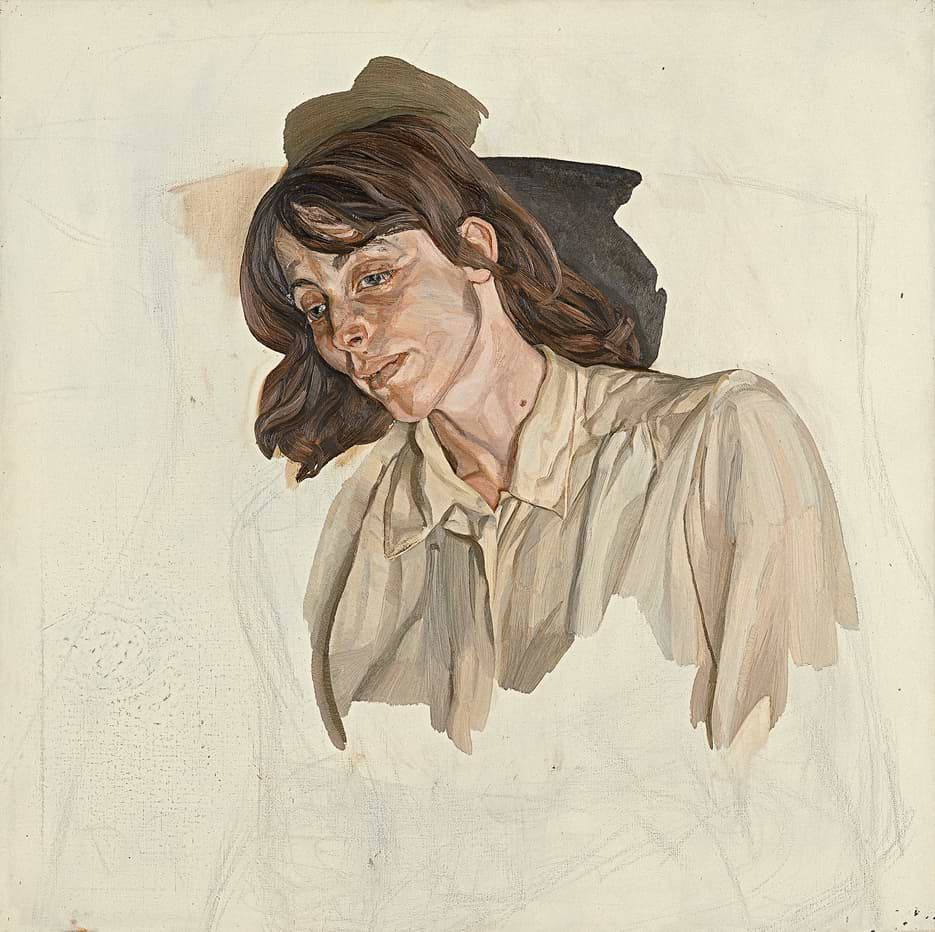

This idea came from my experience ‘watching’ paintings by Lucian Freud, which were inert and silent yet could command my attention and move my imagination better than any video waving frantically at me from the internet.

Now how do I translate the experience of looking at a painting, to the screen?

Choosing Tools

The idea that—

“Many people dream of such [an intrinsically rewarding] life, but few attain it for…they never get very good at what they do.”

—was something I was weary of.

Those of us who make creative work have interests all over the show: we want to learn everything and be everywhere at once—if we’re not careful, we fall into the delusion that this can be done.

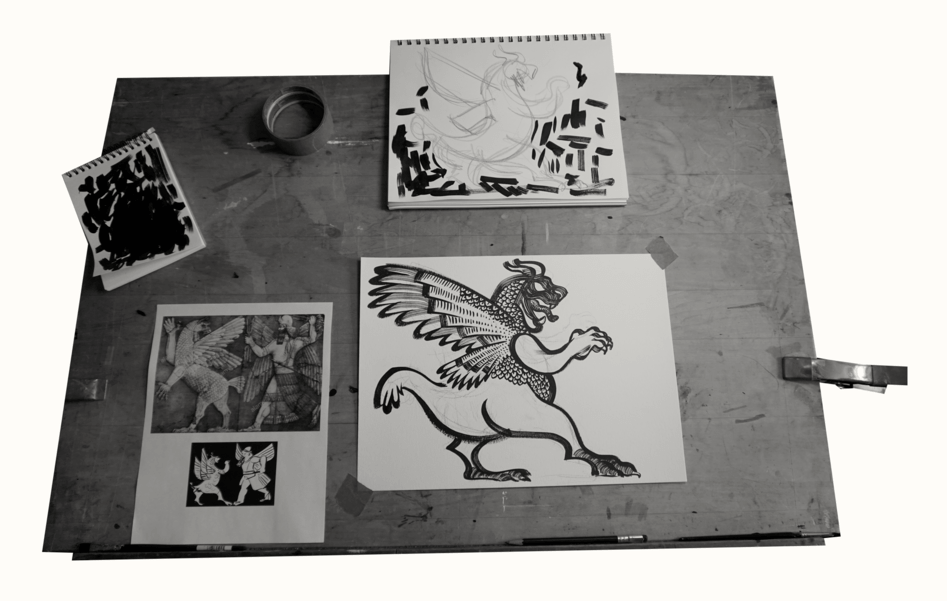

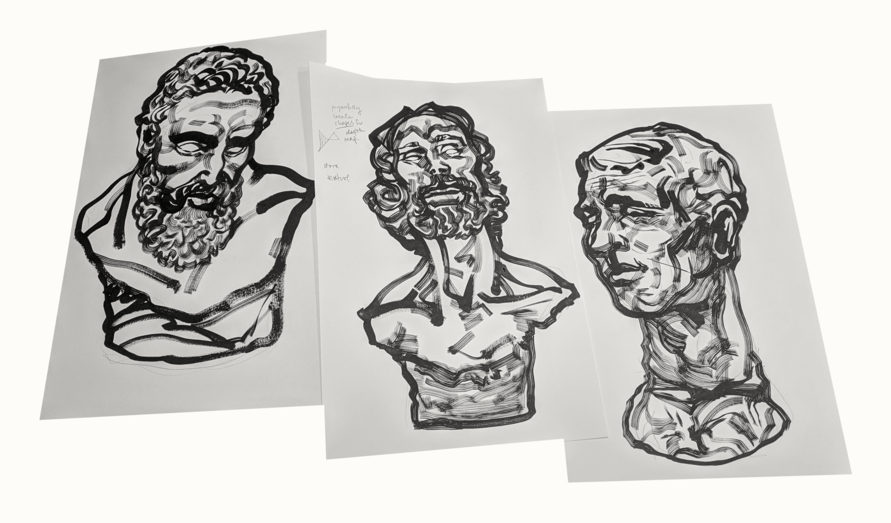

I figured the best way to get “very good” at what I did was to limit the number of things I wanted to get very good at. I picked two tools—traditional ink on paper and a 3D plugin.

The first was costly, because you can’t ctrl+z away mistakes with traditional mediums and the second was something I’ve always felt daunted by: there are so many 3D tools to learn that I couldn’t focus on any. Even if this project never saw the light of day, I thought, nine minutes of animation using these tools was still good practice.

Relying on this limited palette meant all my pictures had a natural consistency to them, and no scene could look too out of place because I was only ever playing with the same two ingredients.

The more I drew and experimented, the better I got at squeezing interesting looks out of my tools, and the more sophisticated the results became.

But the more time I spent on this project, the more I had…

Doubts.

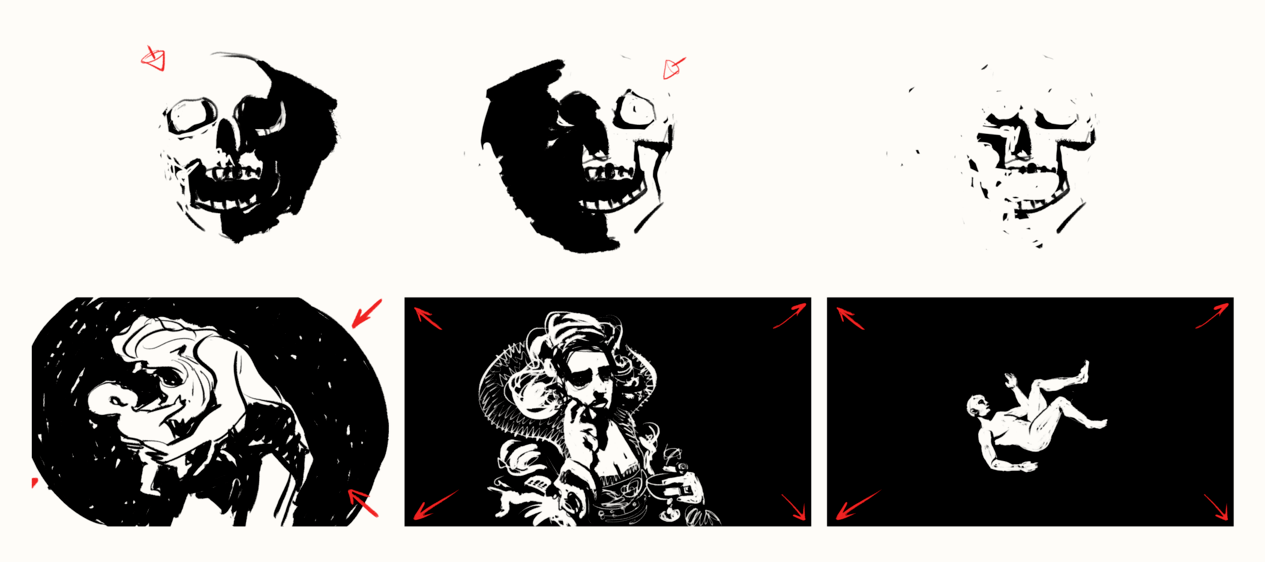

It was month four of this project and I had a smattering of ink drawings, some experiments using the 3D plugin and storyboards I’d shared with the brothers from the Academy of Ideas:

The project was well under way, but because it was a personal project there was no benevolent bullwhip of client deadlines nor the promise of commercial work riches pushing the project forward. I was working in a vacuum—no one needed this project to be done.

When the flash of excitement and drive of making something really cool wore off, all I had were my doubts.

What if the Academy of Ideas doesn’t like the video and won’t end up using it?

Was it smart to spend hundreds of hours on this video without knowing what I was going to get out of it?

What if I run out of steam and can’t finish it?

In those moments, this line seemed pretty glib:

“Even if we make no money from our projects, and even if not a single soul acknowledges our efforts, we will still benefit from this active way of life…” (yea, right!)

I ran off from the project a handful of times, knowing I wasn’t disappointing anyone because no one expected me to finish it.

And yet, every time I ran off, da Vinci’s ghost would come back to haunt me:

“A well-employed life is one in which we choose intrinsically rewarding projects and consistently put in the time necessary for their achievement.”

Wouldn’t it be ironic if, having committed to the project, I couldn’t put in the consistent, enduring effort to see it through? If I was making a video about “relentless rigor” and “consistent effort”, shouldn’t I practice what I was part of preaching?

I couldn’t swallow the hypocrisy, so I would trudge back and take up the script once more.

One picture at a time

When I’d exhausted my doubting, thinking, anxious brain, this line always came into focus:

“Most of us…are not fortunate enough to have wealthy patrons fund our creative endeavors, [but] a small amount of time devoted daily to a creative pursuit…will over time cumulate into impressive results and open up unforeseen possibilities.”

So that’s what I did. Accepting that I couldn’t figure out where I was going with the project, I set aside two hours every morning to spar with it anyway.

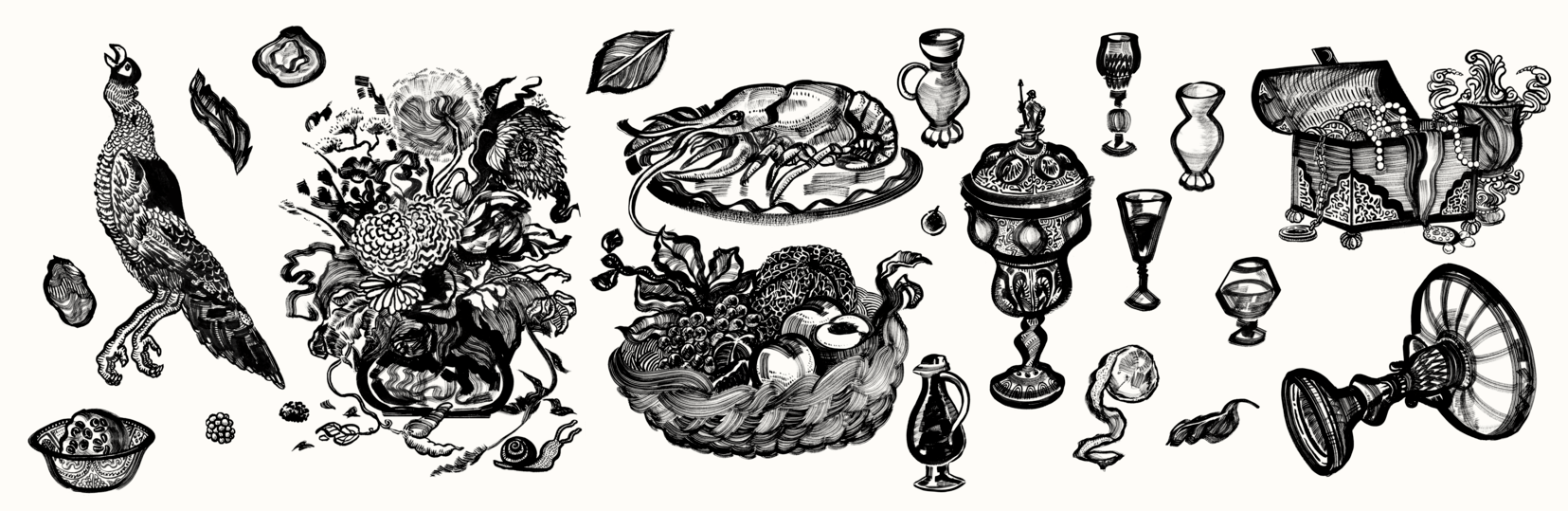

Every idea in the script was first paired with a visual—the “wealthy patron” recalled, for me, 17th century Dutch still lifes which patrons commissioned to show off their prosperity. At the same time, although the objects depicted in the paintings suggest wealth, the artists who spent their lives making such paintings were not themselves wealthy (Vermeer and Rembrandt both died poor).

With the visual idea in place, the next small step was to draw, individually, all the pieces that would go into this still life:

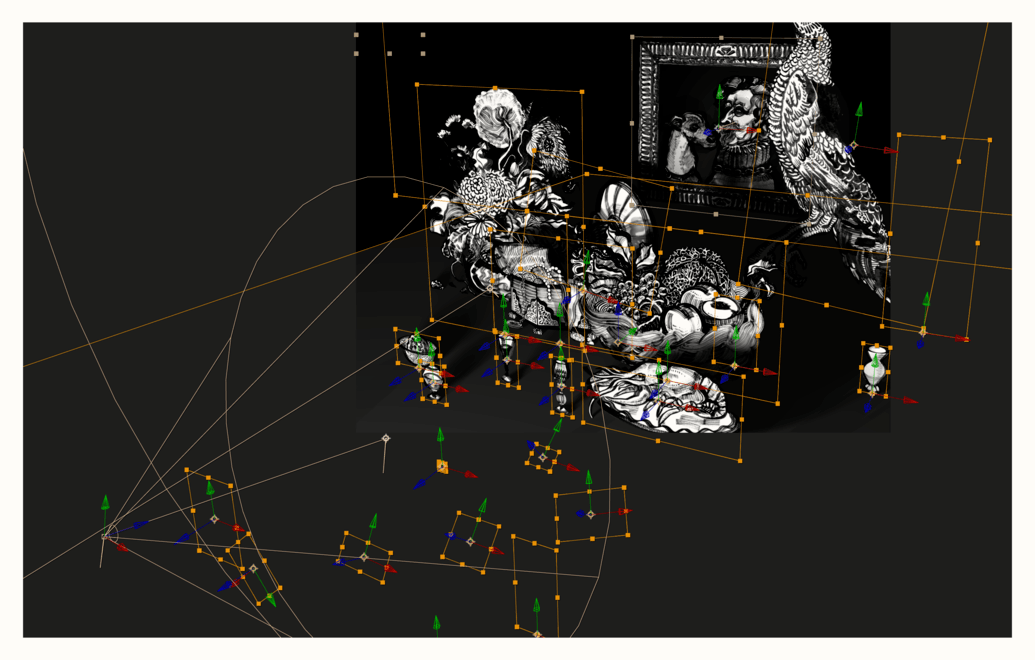

After a week of drawing, piece by piece, each object was scanned, cleaned and placed in 3D space, mirroring how they might have been arranged as a still life on a table:

As we pushed into the scene, I wanted this crowd of objects to fade and give way to a staircase seemingly to nowhere—a staircase to “unforeseen possibilities”.

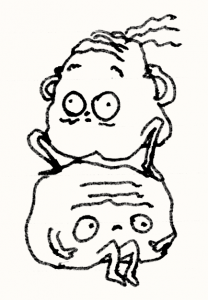

Putting in a couple hours each day eased my doubts and gave space for each picture to grow up organically. The scene above gradually built up a life of its own and demanded a portrait and a set of Fu Dogs I hadn’t intended to draw at the outset:

Each picture echoed the principle set forth in the script—that small, daily efforts grow into complex, unexpected results. Every picture in this project grew up this way, without my knowing exactly how they were going to look until they announced themselves as complete.

Flow

The final promise in da Vinci’s guide to a good life is the possibility, when one is engaged in creative work, of attaining ‘flow’:

“A state of flow is not accessible on command, but instead emerges spontaneously when we are fully engaged in activities that require us to make use of our skills to a maximal degree.”

Given the ongoing struggle with the tools I’d chosen and the uncertainties I had around the project’s outcome, most of the time making this work was definitely not spent in flow. I spent somewhere between five and seven hundred hours on this project; less than fifty of those hours I can recall as flow-y.

Those rare instances of flow were times when my conscious, thinking and planning brain was exhausted by its own cleverness and finally went offline for a little while. That was when I could listen to the dictates of the picture in front of me, adding to it what it still needed, taking away what was unnecessary and allowing the picture to grow by itself, without my conscious demands that it grow into something pre-defined and pre-approved.

These were the times da Vinci gave me a nod and a wink from beyond the script.

In Closing

A year and a half later, the project is finally finished.

Every picture I created for the piece not only reflects the ideas spoken aloud in the script, but was each of the ideas put into action. The “relentless rigor” da Vinci encourages sounds tasty to the intellect but is, in practice, very uncertain and uncomfortable. Comfortable or not, adopting these ideas seriously in your work (or life) does shape the outcome. We can each decide whether or not it’s for the better.

This project is the result of following da Vinci’s Guide in my own small way. I still don’t know what—if anything—will come from finishing this project, but I’m pleased with my efforts, and that’s good enough for now.

Here’s to all the unforeseen possibilities our efforts clears the way for us to see.

Thank you Michael from The Academy of Ideas for taking a chance and letting me spend eighteen months on this one video. You’re a champ.