Creatives tend to be generalists.

We’re inclined to pursue breadth over depth while learning new skills and ideas. We forego the specialist’s clear path forward in a chosen field, instead taking many different paths in finding work most suited to our mix of interests.

Lack of clarity is disconcerting; chaotic, even. So how do creatives balance the tension between interest and competence in a wide array of areas while pressured to find our style, voice and audience – now – and preferably in a way that looks effortless? How do we sharpen and use our generalist proclivities instead of just feeling kinda guilty that we haven’t yet found our specialty?

It starts with this distinction.

There are two types of generalists.

The first is the Effective type. Jean Giraud comes to mind – starting with the Western comic series Blueberry, he went on to work in genres ranging from comedy to sci fi to fantasy, contributing concept art for feature films and founding a magazine along the way. Films from Blade Runner to Star Wars to the Fifth Element owe much of their style and tone to Giraud’s work. The Effective generalist is one who integrates their library of knowledge and skills to contribute new, valuable works.

The second is the Ineffective type. This is the creative who paws at shiny baubles but doesn’t get deep enough into any field. This is the generalist who ping pongs between disciplines but whose expertise is too shallow to be hired for any.

The journey from Ineffective to Effective is every generalist’s great adventure. Chasing after novelty and cooking up new schemes make our identities hard to pin down, but look closely and you will find the patterns to being Effective; patterns that when harnessed will help us leverage our wide-eyed nature as artists.

But first…

Resign yourself to being a generalist.

Stop pretending to be a specialist if you’re not one.

David Epstein’s book, Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World opens with a group of generalists’s discomfort (bordering on shame) as they navigate career shifts. The same concern is ever present: what if we’ll never pick one thing and stick to it? What if we wash up as desperate dilettantes with no career prospects and a swervy soup of a resume?

As generalists we have to accept the kernel of truth in this extreme reality, just as specialists must accept the possibility their specialty will one day be overtaken by bots. The generalist’s diverging paths are winding and murky. But there is great possibility, too – we can tailor pursuits to our skills and interests, as opposed to tailoring our interests to a single, narrow path.

Accept your wide range of interests. Hug them close, listen completely and endeavor to be Effective.

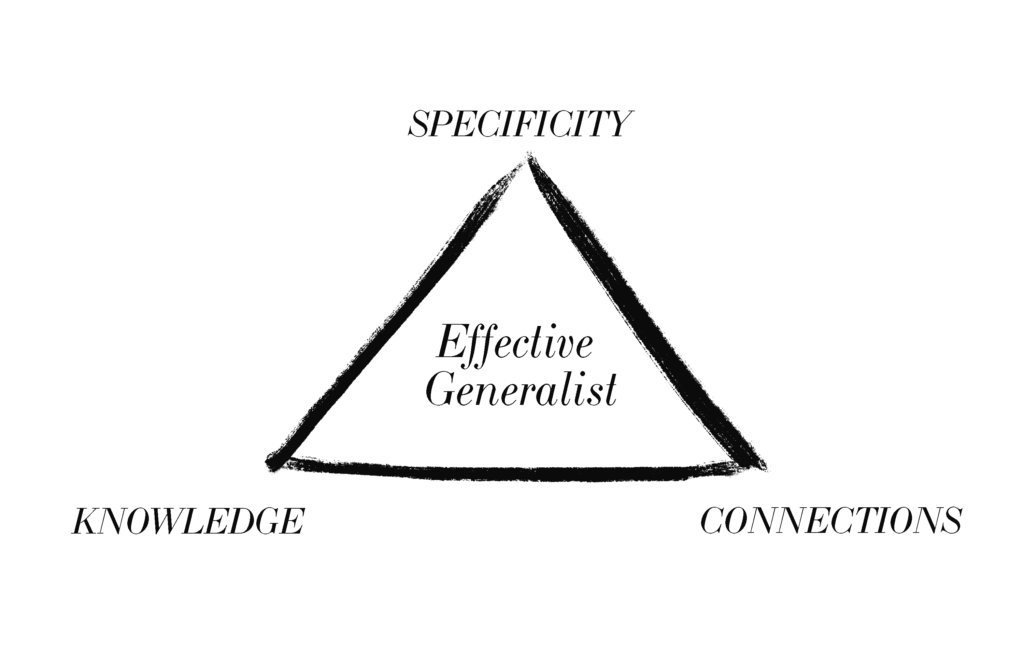

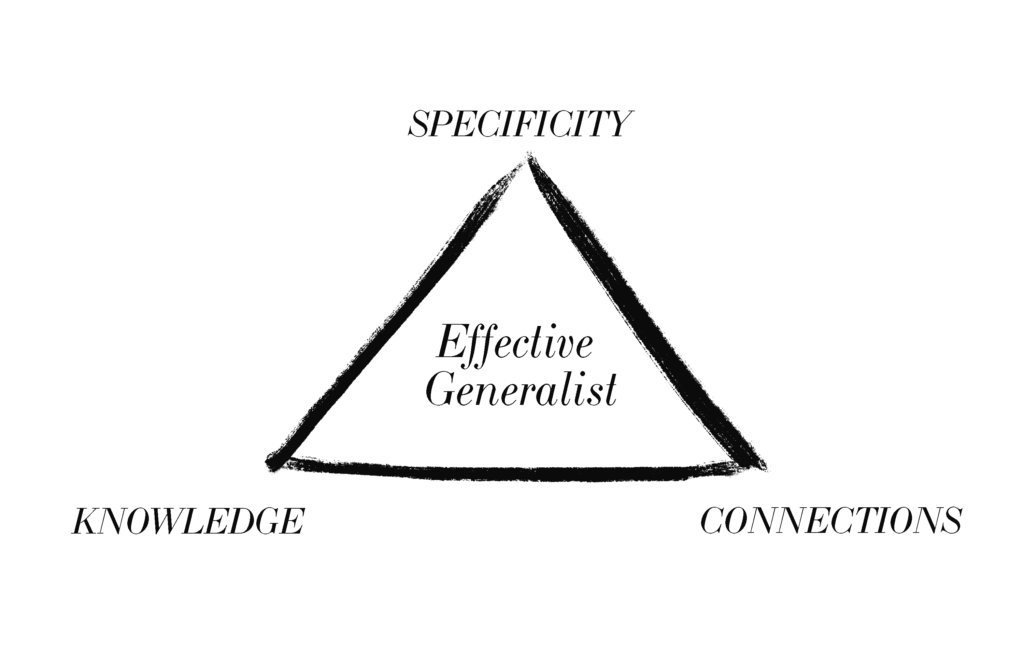

There are three aspects to being an Effective generalist:

We’ll start with “knowledge”.

We’ll start with “knowledge”.

Knowledge: Go broad or go home.

A generalist pursues breadth of knowledge by sacrificing some depth. It’s how we’re wired. Don’t be afraid to learn more about and experiment with all your bizarre interests. The further away from each other your domains of knowledge, the more creative your thinking has the potential to be. That’s the essence of creative thinking: connecting disparate ideas together.

As a teen I threw myself into affiliate marketing, getting paid a commission for selling other people’s products online. At the height of my wheelings and dealings selling CDs and GPS’s I was also learning valuable lessons in marketing and building websites. None of this related to the drawings I was churning out at the time but came in handy many years later when I decided to freelance.

Effective generalists are unapologetic about their broad interests and pursuits. They seek out areas in which they have no expertise. Nobel laureates, for example, are much more likely than even nationally recognized scientists to be “musicians, sculptors, painters, printmakers, woodworkers, mechanics, electronics tinkerers, glass-blowers, poets, or writers, of both fiction and nonfiction.”1

This breadth forms the basis of the second Effective characteristic: forming connections between seemingly unrelated domains.

Connections: Make them in the “wicked” world.

We come up with new insights when we connect expertise from different domains. This is the definition of creative thinking.

These connections are forged in “wicked” as opposed to “kind” environments. In Range, Epstein describes a kind learning environment as one in which patterns repeat and feedback is immediate and reliable. Broadly speaking, the ways in which we learn new skills and knowledge are done in kind learning environments – we take an online course, a live class or watch a tutorial. Trying to thrive as an artist in the art world or throwing yourself into full time freelancing are some ways we cross over into wicked environments which, by contrast, have neither repeating patterns or reliable feedback.

Problems that arise in wicked environments are not solved by any tidy lessons from the kind world. With full time freelancing, one of the biggest questions is – how do I consistently land clients? The scope of the question and its messy ambiguities cannot be answered by any one class or tutorial – the answer to such a question lies in your ability to draw useful connections between the knowledge you’ve accumulated. It wasn’t until I ventured into the wicked world of freelance that I started to make connections – out of necessity – between the things I knew about marketing, websites, and animation. What I had thought of as teenage years misspent in the most nerdy of ways ended up being one of my biggest assets going into business for myself. Failing to make connections between our broad fields of knowledge leaves us with knowledge silos, and we cannot pit a shallow silo against a specialist’s depth.

It’s these connections that propel us ahead of the curve, surpassing even specialist teams: “Individual [comic book] creators started out with lower innovativeness than teams … but as their experience broadened they actually surpassed teams: an individual creator who had worked in four or more genres was more innovative than a team whose members had collective experience across the same number of genres.”2

With our expansive knowledge and useful connections drawn, we’re well on our way to being Effective generalists. Now we’re ready for the final act; the last piece in our Effective generalist trifecta.

Specificity: Be specific, not specialized.

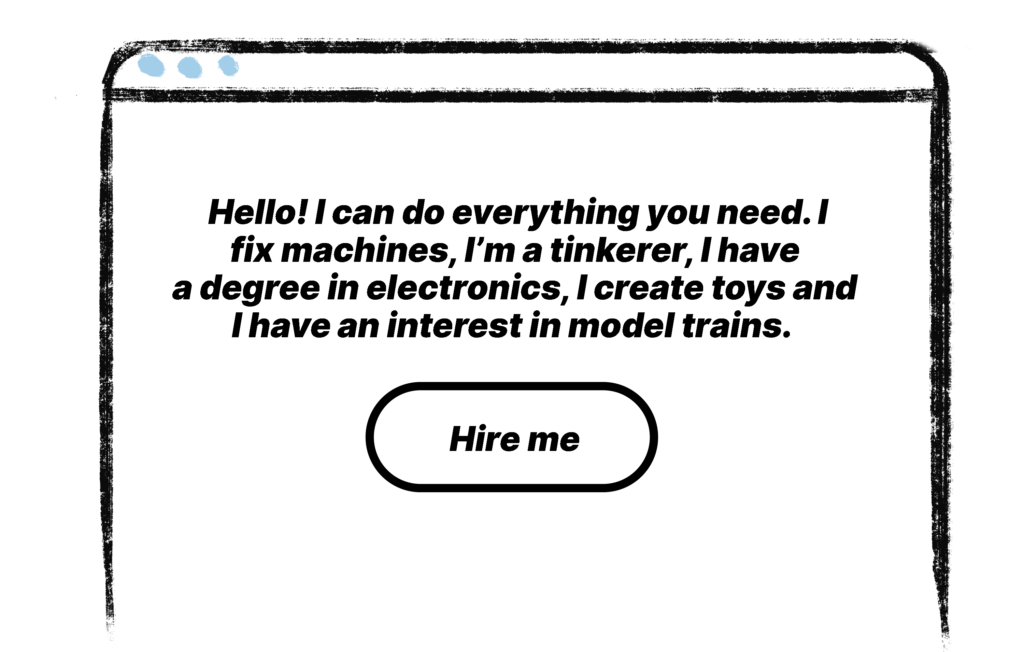

Being a generalist doesn’t mean being vague. My first portfolios were arrogant bits of online real estate billing myself as artist, caricaturist, animation queen and web designer. You can spot an Ineffective generalist’s portfolio a mile away as you read off the artist’s talents like a shopping list. Presenting ourselves like this fails to make a point; we don’t bring anything new, specific or valuable to the conversation.

Listing out a collection of skills and interests like drawing, poetry and web design is merely describing one’s potential. Combining and assembling them into something specific requires you to give form to that potential. This is what we’re attempting to do when pursuing personal projects:

It’s the process of creating specific, standalone projects that is the act of walking along the path from Ineffective to Effective generalist. Without giving form to your ideas, the rubber never hits the road and you’re without wheels necessary to move you forward. Being specific calibrates your next step because being specific gives clarity on what does and does not work. A generalist should not spin up a large web of skills and hide in it. A generalist should keep conducting new experiments with the aim of making specific, valuable contributions.

My favorite generalist profiled in Range is a man who failed to specialize as an engineer and went on to work at a playing card factory instead. He had a slew of capabilities and hobbies ranging from machine maintenance to tinkering to ballroom dancing. If his portfolio read like any other Ineffective generalist’s it would look something like this:

– a vague collection of abilities.

The playing card factory had been struggling for decades in the wicked business world. The company’s president was desperate to innovate and he invested laterally, starting a TV network and selling instant rice among other ventures. He started looking to his employees for new ideas and spotted our generalist, inventing little machines to amuse himself when he had nothing else to do around the factory.

The company president packaged one of these little machines into a toy and rushed it to market. It sold well, and our generalist started creating more toys, each a little more complex than the last. The company calibrated in the direction of toys and pulled their other experimental ventures. Our generalist experimented with various configurations, pulling from his knowledge of model cars, electronics and tinkering. The successes and failures of these first products calibrated his next experiments until he birthed a very specific, very valuable and revolutionary contribution: the Gameboy. Gunpei Yokoi catapulted Nintendo from 19th century playing card factory to one of the largest video game companies in the world.

Specificity is vital to the artist with range. The wicked environment of a failing business sparked connections in Yokoi’s wide skills and knowledge, causing him to create specific experiments – first rudimentary toys and games, then more complex experiments like the Game & Watch that culminated in the Gameboy. Because he was always taking his “knowledge of everything”3 and channeling it into something specific – as toys, as games – he was able to travel very quickly from Ineffective to Effective generalist.

Keep experimenting.

With this trifecta in mind, we generalists can carve out a niche for ourselves over time. Learn and sample broadly, make connections between what we learn and then integrate our knowledge into specific, usable tools that solve wicked world problems.

There is no predetermined path for a generalist, so we must create our own. We have the opportunity to create a path most suited to our strengths and interests, and we find our niche by continually experimenting. This accordion-like expanding and specifying of our talents allows us to make the journey from Ineffective to Effective generalist, each experiment bringing us further into our path. As Epstein notes, “a diverse group of specialists cannot fully replace the contributions of broad individuals”4, so it is our exciting task to make full use of our generalist talents.

Does this resonate with your experiences as a generalist?

1. Epstein, D. (2019). Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World. Riverhead Books. pp. 33.

2. Ibid., pp. 209-210.

3. Ibid., pp. 198.

4. Ibid., pp. 290.