We don’t find our style or voice by chasing it directly. When we try to make something original, it backfires and we wind up copying work absorbed elsewhere.

Here’s another way of finding originality: look at it as a product of necessity and not just imagination.

Jim McKelvey, glassblower and co-founder of Square, puts it like this: we end up doing original things when we are forced to invent solutions to our perfect problems.

A perfect problem stands at the sweet spot between two problem types: those that are unsolvable, and those that we don’t have the means to try and solve. A perfect problem is an unsolved problem that impacts us directly and that we have “the power and courage to solve.”¹

Let’s look at an example of original creative work born out of solving a perfect problem.

Alegria

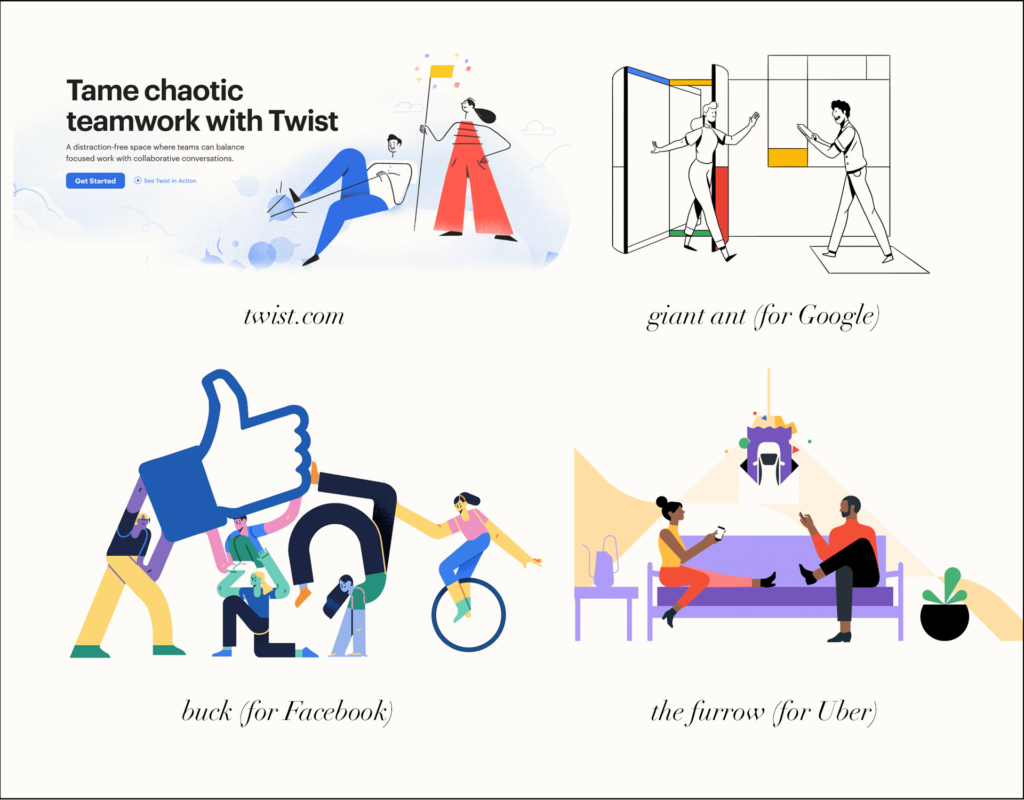

Alegria is Facebook’s illustration and animation system built by Buck in 2017. It was the solution to a key set of problems Facebook was facing (ha!) at the time—they needed to roll out a ton of visual content across their platform and they needed it all to be consistent, fast to produce and usable cross-culturally.

As a visual system, Alegria was not born out of a vacuum. Facebook didn’t come to Buck to make a “cool and colorful” style for the tech giant. Facebook needed Buck to solve a burning set of problems.

The agency got to work and developed Alegria, a visual language that systematically solved each of Facebook’s problems by using:

- Flat, minimal and geometric shapes. Basic shapes are universal and thus easy for multiple artists to adopt. There are few Michelangelo-esque draftsmen, but most artists can draw a circle and a square. Fewer elements and fewer colors also mean fewer choices, which leave fewer opportunities for misinterpretation. A style guide with a handful of colors and basic shapes makes it easy for studios all around the globe to adopt.

- Figures with non-representational skin colors. Facebook hit two billion users in 2017, so it was crucial to introduce a visual system that could represent, without alienating or offending, this enormous and growing userbase.

- Figures are stylized and anatomically imprecise. The bendy-ness of Alegria’s characters give enormous leeway for different artists to adopt and still have the illustrations feel like they belong in the same family. The imprecision of the style also gives leeway for animation—stylized characters do not have to obey a constrained set of guidelines for how they move, and this freedom allows multiple artists from multiple studios around the world to work in this visual system while outputting work that is consistent.

Alegria became an original and hugely successful solution to Facebook’s perfect set of problems. It was so successful that any illustrator or animator working in the field today either works in, or has worked in, the Alegria system:

All of this is to say, when we next feel our work is lacking originality, instead of trying to imagine ourselves to new worlds and new ideas, we could turn to identifying and then trying to solve our own perfect problem instead.

So…

How do we find perfect problems?

Some problems don’t bother us.

Some problems bother us but are beyond our power to solve.

Some problems bother us and have already been solved.

And then there are a handful of problems that bother us, that we can do something about, and that there are no current solutions for.

This last category is where we’ll find our very own perfect problems.

If we take these on, we’ll inevitably have to invent some new solutions to smaller problems littered along the way, and in inventing these new solutions, we will be forced to produce something new. This “something new”—or rather this accumulation of small, necessary inventions—might then be termed our style or our voice, but it’s really just the solution that’s organically grown out of solving all the smaller problems within the umbrella of our larger, unsolved, perfect problem along the way.

But in taking on our perfect problems, Jim McKelvey warns, we are leaving the walled city. We cannot rely on existing solutions, because by definition a perfect problem is one that hasn’t been solved before.

Outside the walled city, there is no one qualified to solve the problem we’ve taken on because we can only ever be qualified to do something that’s been done before. This is deeply uncomfortable. We’re wired to copy what’s known to have worked before, and we’re conditioned to seek tutorials and qualifications for a new thing we want to try before actually trying that new thing.

Alongside the discomfort is excitement, too. “Copying almost always feels comfortable, but it will never produce the thrill of invention,”²—in trying to solve our perfect problems, we start to live an exciting life.

Practical reasons for solving perfect problems

Most of the time, in most domains of our life, there’s no reason to look for and try to solve our perfect problems. Why? Because most of the time, for most problems, copying someone else with the right solution works great.

Take Alegria as an example—a ton of fantastic motion design work today are variations on its minimal, colorful and gangly-limbed themes. This also means that if you are an illustrator or designer looking for work, you just learn this system and you will be pretty much guaranteed client gigs.

However, copying has a serious downside: it doesn’t produce anything new. As creatives, we are drawn to and nourished by the new and unexplored. Prolonged copying without trying to solve our own perfect problems lead to us being cynical about and disillusioned by client work. Client work has us solving someone else’s perfect problems, which we’re motivated to do by external rewards like money or reputation. This external reward system is necessary, burns brightly, but burns out fast. It’s very different to that internal satisfaction we get from tackling problems dear to us.

Further, perfect problems makes us stop fetishizing qualifications. A lot of us want to be certain we are qualified for a project or job at hand before we’ll even try it. Whenever we want to do something new, the first thing we look for are tutorials and courses telling us how to do that new thing.

This is fine when we’re within the walled city. Inside the walled city, everyone copies and qualifications make perfect sense: we learn from others how to be an illustrator, an animator, a graphic designer, before we’re qualified to be hired as one ourselves. We copy how others fly planes before trying to fly one ourselves. It’s often counterproductive to try and reinvent the wheel, so we don’t.

Stepping outside the walled city, qualifications mean little, and “if you are waiting for qualification, you can only ever be qualified to do something that has already been done.”³

The beauty of solving perfect problems

- McKelvey, J. (2020). The Innovation Stack: Building an Unbeatable Business One Crazy Idea at a Time. Portfolio. pp. 7.

- Ibid., pp. 93.

- Ibid., pp. 245.