“I must be sincere towards what I am. … Experimenting is the only thing that fills me with enthusiasm. … It is the only sphere where I feel really honest and sincere.”

—Orson Welles

This is part II of my Bukowski Project case study where I’m tackling a personal project with the aim of finding a less “controlled” process of creating work. You can read the first part here.

The journey so far: make random blobs on the page and free associate to come up with coherent scenes and characters.

I ran into a problem.

I got wrapped up in the fun of discovering these scenes and characters. The blobs were getting out of CTRL. Instead of moving forward with the project, I kept using chunks of time to self-administer rorschach tests. Part of the fun was avoiding the next steps in the project. This is similar to the guitarist who learns a few songs and plays them over and over again for years without pushing for improvement. (This may or may not be me – who can say?)

Picking up a pen and doodling for an hour is fun. Playing songs you already know on the guitar is fun. But personal projects aren’t designed for fun. They’re opportunities to keep finding more truthful answers to the questions “what is it I most want to express?” and “how do I best express it?”. This is more fulfilling than fun.

What’s My Next Step?

How do we distinguish between busywork versus a valuable next step that will actually propel us forward?

A good gauge is whether we feel comfortable about the next step. Let me explain.

By now I had a bunch of assets to play with. I could easily have fooled myself into creating more assets – why not create enough assets to use for the entire poem? After all, I was having fun and feeling productive.

The tiny voice in the back of our heads knows, though.

This process was getting a little too comfortable and slipping into busywork. Instead of figuring out whether these assets actually worked when paired alongside the poem, I could ignore that (essential) part and keep indulging in the fun of drawing more stuff.

I peered down the alternative path. This was one in which I started compositing the assets I had to see if the images and the text worked together in context. This step was met with a lot of resistance – part of me would rather not risk exposing my pretty images to the judgment of the project.

It was decided, then!

Compositing was the next step. Seeing the images together with the text would force me to confront whether the images I created could be used.

Here’s a terrible rule of thumb: a task is only as valuable as it is uncomfortable for you. Our comfort zones are small pools where the fish are all dead. It’s no place to nest.

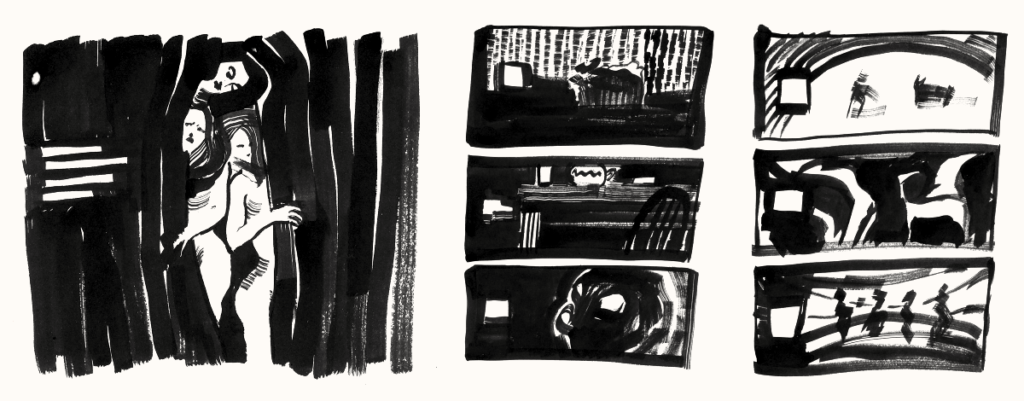

I made some thumbnails to give me guidance:

I usually made thumbnails at the beginning of the image-making process but found it throttled idea generation. I tended to let them dictate what the final piece looked like. So I held off making them until having structure and a cohesive narrative was absolutely necessary in order to progress.

Making thumbnails later in the process allowed me to use them as tools to help build pictures with instead of tools with which to generate ideas. This is a useful delay, especially if thumbnails are starting to dictate your ideas instead of the other way around.

I prepared to scan and edit my images.

Preparation and Experimentation

Whether you’re a freelancer or work at a studio, under the crunch of deadlines and budget it’s hard to find the time and courage to experiment. But if we take the position that we know very little about what it is we want to express creatively, the only way to find out is to run consistent experiments on our own time. Personal projects are such experiments.

Where were we?

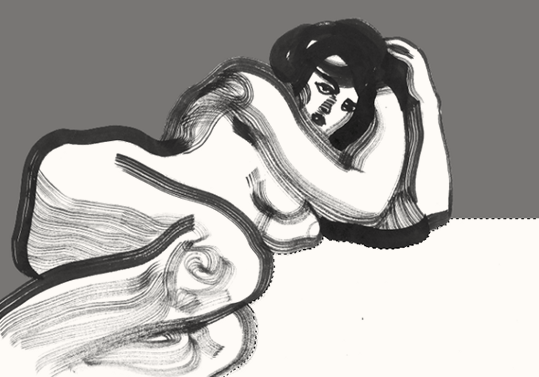

Right. Back to the images that emerged from blobs.

I scanned and cut them out:

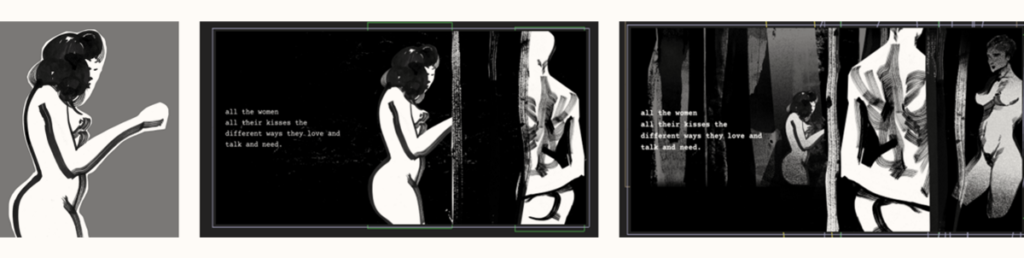

I laid them out in After Effects, playing around with their placements:

(Ladies chillin in a forest)

There’s an excitement when elements come together in ways you don’t expect; an image sometimes isn’t a result of your clever calculations but emerges from the page:

(Composition experiments)

Just as clients sometimes have to see the wrong solution before they’ll go with the right one we insisted in the first place, so it is with our experiments. We’ll never know whether something works until we risk ourselves – our effort, time, resources. Making sure we’ve got the perfect composition in our head before committing it to the page is the wrong kind of time wasted because there’s no action. Commit something to the page first and experiment with it until it feels right. It’s paradoxical, but the more we can learn to trash most of our efforts, the faster we’ll find something truly original and valuable in our work.

As I watched the compositions form, I felt there was something right about using the bulls as motifs for the women in the poem. It’s the same feeling when you don’t thoroughly understand a novel or film but still feel it to be true. The bulls were some of the first images to emerge in this project and struck me as being central to the poem. For a time I was worried it didn’t bear connection with Bukowski’s poem but as I’ve drawn more assets the centrality of the motif hasn’t gone away.

So I’m keeping the bulls.

Have you read Marie Louise Von Franz’s The Way of the Dream? In it she comments on Jung’s concept of the anima and animus. The anima is the woman within men, the animus the man within women. There are positive aspects of the masculine within women (courage, intellect, drive) as there are negative (stubbornness, recklessness, unrelenting criticism). In this case, the bull seemed an apt metaphor for the strong and volatile animus when a woman is “taken” or “fooled”.

Now that I’d experimented with some initial compositions, I threw away the drawings (not literally – they’re resting in a drawer somewhere) that didn’t work and used the ones that did as the benchmark for the rest of the assets.

Continuing with asset creation

“I don’t believe in learning from other people’s pictures. I think you should learn from your own interior vision of things and discover, as I say, innocently, as though there had never been anybody.”

Orson Welles

I’m on an Orson Welles kick.

In the spirit of experimentation (and not imitation), I continued drawing and compositing scenes without referencing other artists’ work. No Dribbble, no Behance, no scrolling up and down the Instaz.

This proved tough.

We always want to know we’re “on track”. We want to know the things we’re creating are good. We get a kick out of imitation – when we imitate an artist we admire, we get a little buzz when something on our page reminds us of their work. There’s a deep desire to imitate what we find admirable in others – it’s how we learn our craft. But imitation eventually must be risked for our own “interior vision of things”, and that means letting go of the buzz and entering into virgin lands.

I first got exposed to this idea through Nicolas Uribe, who is most known for his sketchbook paintings (yes, that’s oil on paper!). He says (and I’m paraphrasing) that when we’re figuring out our voice, we subconsciously scan our work and match it with what’s “good” or “worthy”, a standard based on a database of work we’ve consumed via the internet, books, galleries and social media feeds. We then make work that’s no longer true to our vision. We try to bypass the stress and uncertainty of creating original work by creating pictures that remind us of stuff we’ve stored in this mental database. Then the creations no longer come from us - however imperfect or bumbling - but become clones of other artists’ works. On some level we know we’re living in the space artists before us have carved out and we dare not step outside.

Here’s how experimentation slips into imitation.

While experimenting, I’d come up with a composition that struck me as something interesting I’d not seen before. I couldn’t compare it to my mental database of “Good Work” because it looked nothing like stuff in this database. That’s a strange place to be.

The discomfort of not knowing whether an experiment is any good might cause us to default to a safer solution that’s worked for us in the past. We draw a scene using a perspective system we’re comfortable with; we draw a character whose features we’ve drawn before.

These are quick sleights of hand that allow us to couch on skills we already have, and make images that imitate stuff in our mental database. This is comfortable but doesn’t push us to satisfying results.

What’s the alternative?

I had a pile of index cards from an enthusiastic trip to Staples and I thought: what if every time I came up with a novel idea that’s outside my mental database of “Good Work”, I wrote them down? Instead of tossing out foreign ideas (and the challenges they bring in tow) in favor of familiar ones, I could actually spend some time with the ideas and consider them. On the back of my card I would write down new tools or knowledge I’d need to acquire to realize the idea.

Breaking down new ideas like this gives our brain a plan, and a plan gives our ideas a chance to get born.

Taking stock

At this point I’ve drawn assets for three of the ten or so panels envisioned for the project. The next step is to start reaching out to web developers and get a sense of how these images could come together as an interactive website.

Stay tuned.