I don’t use social media. If you like what’s here, stay updated on creative freelancing tools and ideas by subscribing below.

The Opportunity

Make More Money, Work Less and Do More Personal Projects.

We’re in new territory.

Everyone is working remote, freed from long commutes and the distraction of open offices. The 9-5 with art directors and producers looking over shoulders making sure work gets done is getting replaced by individual ownership of projects.

All this points to an amazing opportunity:

Remote work allows creative freelancers to set new rules.

We can:

- Make more money by freeing ourselves from

working in-house on hourly or day rates - Work less by batching client work into the

times of day we are most productive - Dedicate long, uninterrupted periods of time

in the day to personal projects.

None of this is theoretical—I’ve been living out these principles as a remote creative freelancer for the past five years.

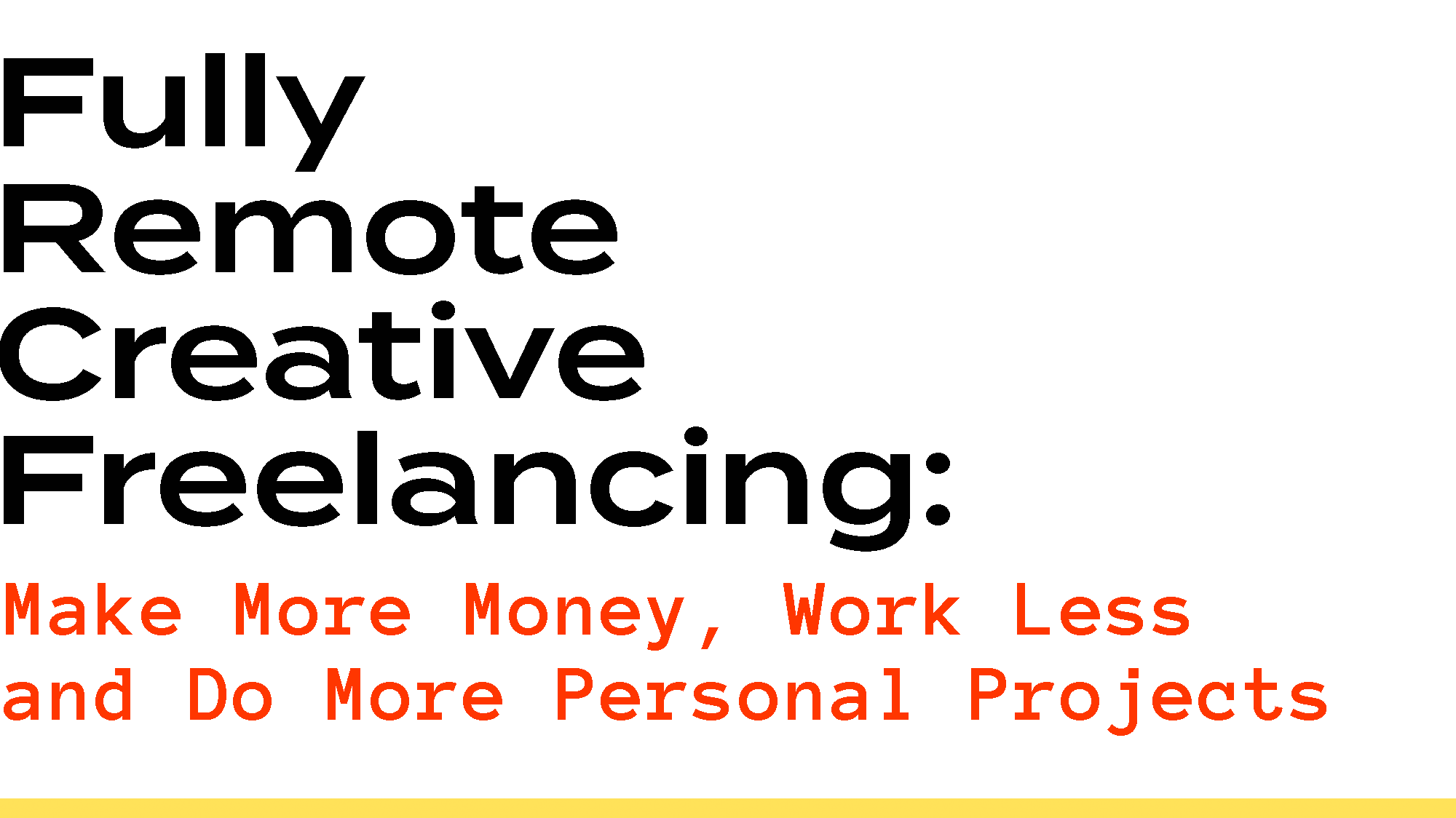

Five years ago I left my full time studio job and I’ve been a remote creative freelancer ever since, primarily doing motion design and illustration work. I’ve gone on to do a range of projects for a variety of clients—from broadcast animations for National Geographic to title sequences for the International Center of Photography to interactive illustrations for Carnegie New York to a lyric video for Kesha:

I thrive on the variety of styles and mediums I get to use with different clients.

These past five years, I’ve gone to work in-house for clients less than four weeks in total.

I work about four months out of the year and make roughly $100k.

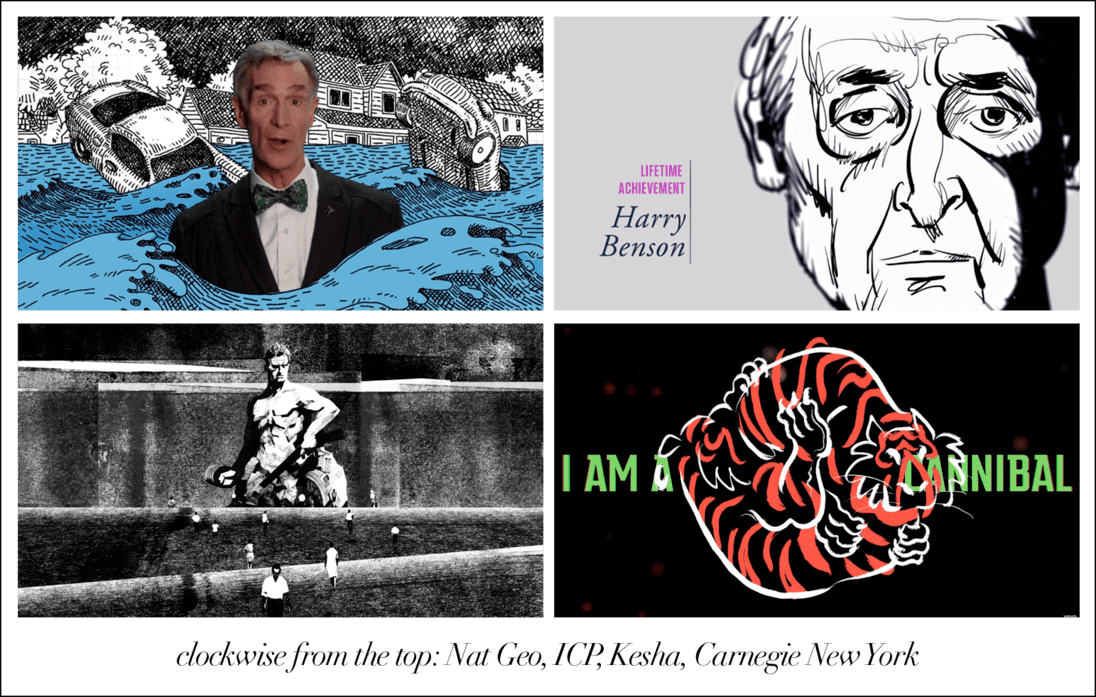

The lion’s share of my time is devoted to personal work: I paint, write and collaborate on creative projects. These projects in turn make me a more versatile freelancer:

Remote creative freelancing can get us into a positive cycle—more uninterrupted hours in the day means we can get client work done faster, leaving us more time for personal projects, which develops our personal creative vision, which over time sets our work apart from other freelancers and increases our visibility to clients willing to pay for original ideas.

We’ll go in depth on each of the steps above in the next sections of this guide. It’s a quick read, I promise.

But first let’s examine what you don’t need to do when you set out to take advantage of this opportunity:

You don’t need to go in-house.

I work way faster in my home office than in-house for a studio, and I suspect that is true for most of us doing creative work.

We should question the quality of work achieved in open offices.

Let’s say we work an eight hour day with a half hour for lunch. That’s 450 minutes of work per day. Of those minutes, we check email or someone asks us a question every twenty minutes or so. That means our workday is divided into twenty-two, 20-minute slices within which we’re supposed to do our best work.

So our best work just doesn’t happen at work.

Creative work needs long, uninterrupted stretches of time to complete. When our time is parceled into tiny chunks, we feel we’re always skating on the surface with notifications and chatter and Seamless lunches, unable to take the deep dives necessary to make breakthroughs.

As a remote creative freelancer, I block out four hours every morning for client work. This is usually plenty of time to get through the amount of work I’d have spent a whole day on in an office.

When we can focus without being distracted, we can do more in less time.

You don’t have to bill by the hour.

Billing by the hour punishes the expertise and speed of freelancers doing creative work.

Let me explain.

A senior designer will finish work faster with less rounds of revision than a junior designer. The former’s experience makes them better able to intuit what a client is really after, and they are more skilled with the tools of their trade. What might take a junior designer five hours to do, then, only takes the senior designer two.

Let’s say the senior designer charges $100/hr, making $200 for the project while the junior designer, who charges $50/hr, takes three hours longer and gets paid $250.

Why should the senior designer be punished for their expertise and speed? Yet this is commonplace in the creative industries.

Being a remote creative freelancer allows us to charge differently. Instead of billing by hour or by day, we can charge by project.

I get paid for the deliverables I send to the clients on an agreed-upon schedule, and my clients don’t care how many hours I’ve put into the project so long as they’re thrilled with the results.

(We’ll delve deeper into this idea a little later.)

You don’t need to use social media to grow your freelance business.

Social media is not necessary for a creative freelancer.

It is just one method of many to get our work in front of potential clients, and it is a highly addictive one at that. It demands constant investments of our attention for (mostly) the gain of the platforms themselves.

A direct email is a much more effective way of getting our work in front of a potential client and there is nothing inherently addictive about email clients.

In the end, the value we bring as artists derive from the quality of our body of work and how capable we are of solving client problems. Social media shifts time away from these areas and trains us to create work appropriate to their platforms—work that is short, bite-sized and shallow. Snacks.

To be successful in the long-term as artists (freelance or otherwise), we can’t just make snacks. We need to work on substantial, difficult projects to attract the kinds of opportunities that excites us.

But enough about what we don’t need to do. Let’s take a closer look at what we should be doing to take advantage of the remote creative freelancing opportunity.

How to Make More Money and Work Less.

Charge by Project.

We touched on this briefly when I suggested we stop billing by the hour.

When we sell our hours, the amount of money we make is capped by the number of hours in a day. Charging by project removes that cap, allowing us to make more money, work our own hours and build relationships that benefit both our clients and ourselves.

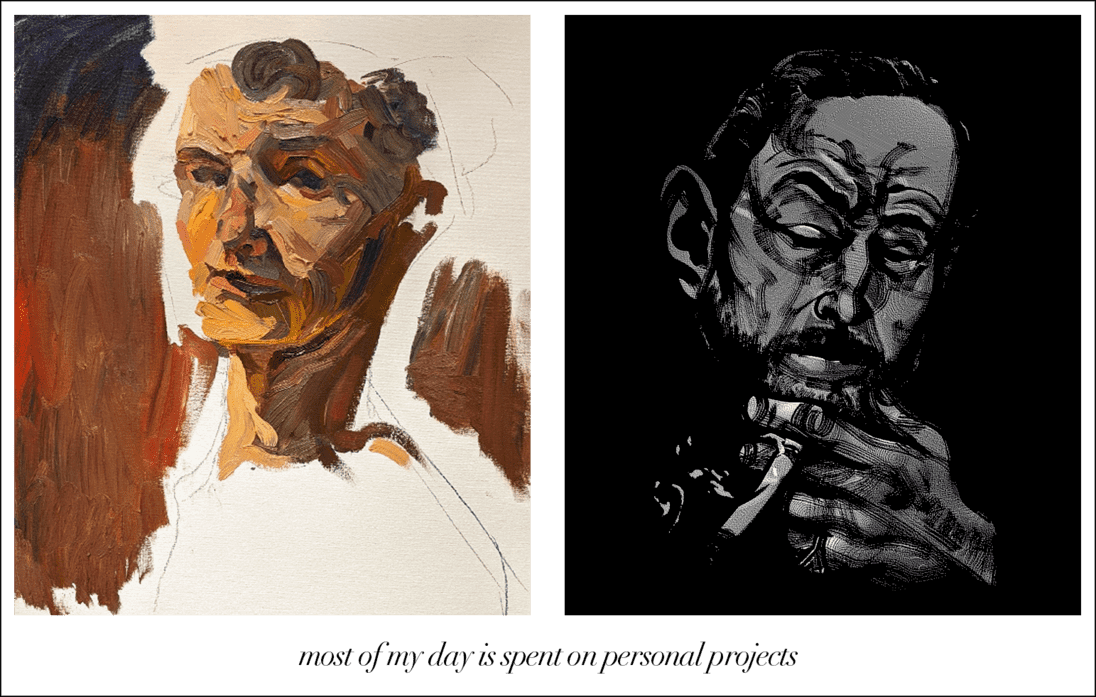

Charging by project means we can take on many projects simultaneously. Since creative projects often have periods of lengthy radio silence as we wait for client reviews, instead of idling at an office we can use that time to slot in work for other projects:

In addition, we don’t have to commute and sit in an office for eight hours straight. We can pick the most productive hours of our day to get client work done.

Lastly, when we charge by project, we set expectations that benefit both the client and ourselves.

The client:

- Has an expectation for what will be delivered

- Has an expectation for when they should expect deliverables, and when they need to give feedback

- Doesn’t have to micro-manage what you are doing with your hours.

Freelancers can:

- Focus and get the work done quickly

- Work at times of day that suits us

- Take on multiple projects simultaneously.

We’re happy, because we’re making a lot more money for the same amount of time and the clients are happy because they get quality work without having to micro-manage how each of their freelancer’s hours are being spent.

Both parties are happy and motivated to work with one another. Over the past five years, each of my clients have become repeat clients.

Control Your Environment.

We can get more done in less time if we maintain a work environment free from digital and real-world interruptions.

Two hours of uninterrupted, focused time is the equivalent of five hours spent in an open-office with all its daily distractions.

When we work remotely, we can better control distractions and dedicate uninterrupted chunks of time necessary for creative work.

We don’t have to respond to questions right when someone asks them. Art directors or producers can’t come and “check in” whenever they have a free minute. You don’t have to blast music or podcasts all day long to drown out the phone calls and conversations ongoing in an office. We can batch emails to certain times of day. We can turn off Slack. Close the door.

Freed from distractions, we can work quickly without losing quality. We can do client work in the early morning and have the rest of the day to ourselves.

Control Your Time.

Remote creative freelancers get to choose when we work by when we are most energized mentally.

Typically I’ll schedule client meetings and reviews in the afternoons, leaving my most focused morning hours to difficult creative work that requires my full attention.

Controlling time means we never have to work overtime, and we always always build time in the day to pursue our personal work. This last point is essential to staying a successful creative freelancer over the long term, and I’ll elaborate why this is in the last section of this guide.

I organize my days and tasks using this simple Notion template. I outline my projects, create tasks out of each phase of the project, then dump each task into a day in the calendar. Each day I just look at this one page, which pulls all the things I need to do for the day. At the end of each week, I’ll recalibrate based on what I accomplished in the week and repeat the process.

A simple schedule is essential to the remote freelancer. Unstructured time is otherwise quickly eaten away by Netflix, Age of Empires or staring at pets.

Finding Clients Willing to Offer Remote Work.

Kill the Generic.

As a remote creative freelancer, one of the first (and only) point of contact between us and a potential client is our website.

Our website is an indication to the client of how well we can communicate—visually, through our work and how we’ve built our site, but also verbally, through the copy on our site.

Most freelancers fail to see their websites as a means of communication; they think they ought to have a website because all their peers have one. This is a mistake. If our website looks like everyone else’s in our industry with the same words, pitch, work—we’ve effectively painted ourselves in stripes and disappeared into the herd. Why should a client hire me over the next freelancer?

Working remotely means we have little or no opportunity to show our personalities in person (I have only met a minority of my clients in person), and if all they have to go on is our website and our email correspondence, those means of communication become heavily weighted in their choice of who to work with.

Each means of communication with the client should reveal something specific about who we are as artists; we should take care to avoid any vague statements that litter portfolios like so many dandelions:

I get it. I love things too. But these phrases tell the client absolutely nothing about who we are as an artist or as a freelancer.

Instead, we can watch the ways we do things differently to our peers—not to be contrarian, but in an effort to figure out what is genuinely different and useful about our services.

You might quicker than most.

Perhaps you know how to code, as well as design.

Maybe you know how to illustrate, as well as animate.

Show the client why they need to work with you and not the freelancer over on the next tab they’ve got open.

This brings us to another important idea:

Don’t Start from Zero.

I was reviewing a student’s portfolio—she was transitioning into interactive design, but had worked in the corporate world for the past ten years. Her portfolio was clean and the work was professional.

But nowhere on the site did she mention her corporate experience.

I asked why she didn’t want to point it out?

She said she didn’t feel it was relevant to her role as an interactive designer. So instead of incorporating or even mentioning her experience, she cut out that part of herself and made a website that was no different than most other interactive designers.

There’s an intrinsic fear to being different. In the case of making a livign as a creative freelancer, though, that fear must be overcome. If clients don’t feel our work is distinctive, we will have a difficult time landing work.

Instead of throwing away our real life experience because we look around and it doesn’t match what our peers appear to be saying, we should carry it over into our new pursuits, highlight it and sell it as a strength.

My student’s experience meant she had insight into the corporate world that most other interactive designers do not have. She was accustomed to presenting ideas, revisions, budgets to higher-up decision makers. She knew the corporate lingo. She knew how long things in the corporate world take.

A marketer at a large corporation looking for an interactive designer would feel immediately at ease with someone of my student’s background, and that bit of extra familiarity is often enough for a client to take a chance on us.

Never start from zero if you can help it. Always try to integrate all of the skills and experiences you’ve accumulated over your life—these are what make your services distinct and memorable.

Remote Expectations.

We should be aware of some expectations for remote work: some clients are open to it, others not so; some types of work lend themselves to remote work and other types do not.

We should focus all our energies on finding and pitching clients who are already open to working with remote freelancers, and we should be aware of whether the type of work we want to do is suited to being done remotely.

If we want to be remote creative freelancers, we should expect to do self-contained projects with a high degree of autonomy. Illustration work is a good example. Knowing this is key when we are trying to find where we can situate ourselves as remote creative freelancers, and not waste time pursuing roles that are too collaborative to be remote.

My preferred choice of finding remote clients is to look for agencies and studio with already distributed teams, and let all of them know in my initial email I am a remote only freelancer. Pitching our services to remote-friendly clients is a win-win for both the client and ourselves: these agencies want to find artists who thrive on remote work, and we don’t need to try and convince a company to work with someone remote if they don’t have practices in place to facilitate that in the first place.

Make Personal Projects to Attract Better Clients.

Make finished projects, not exercises.

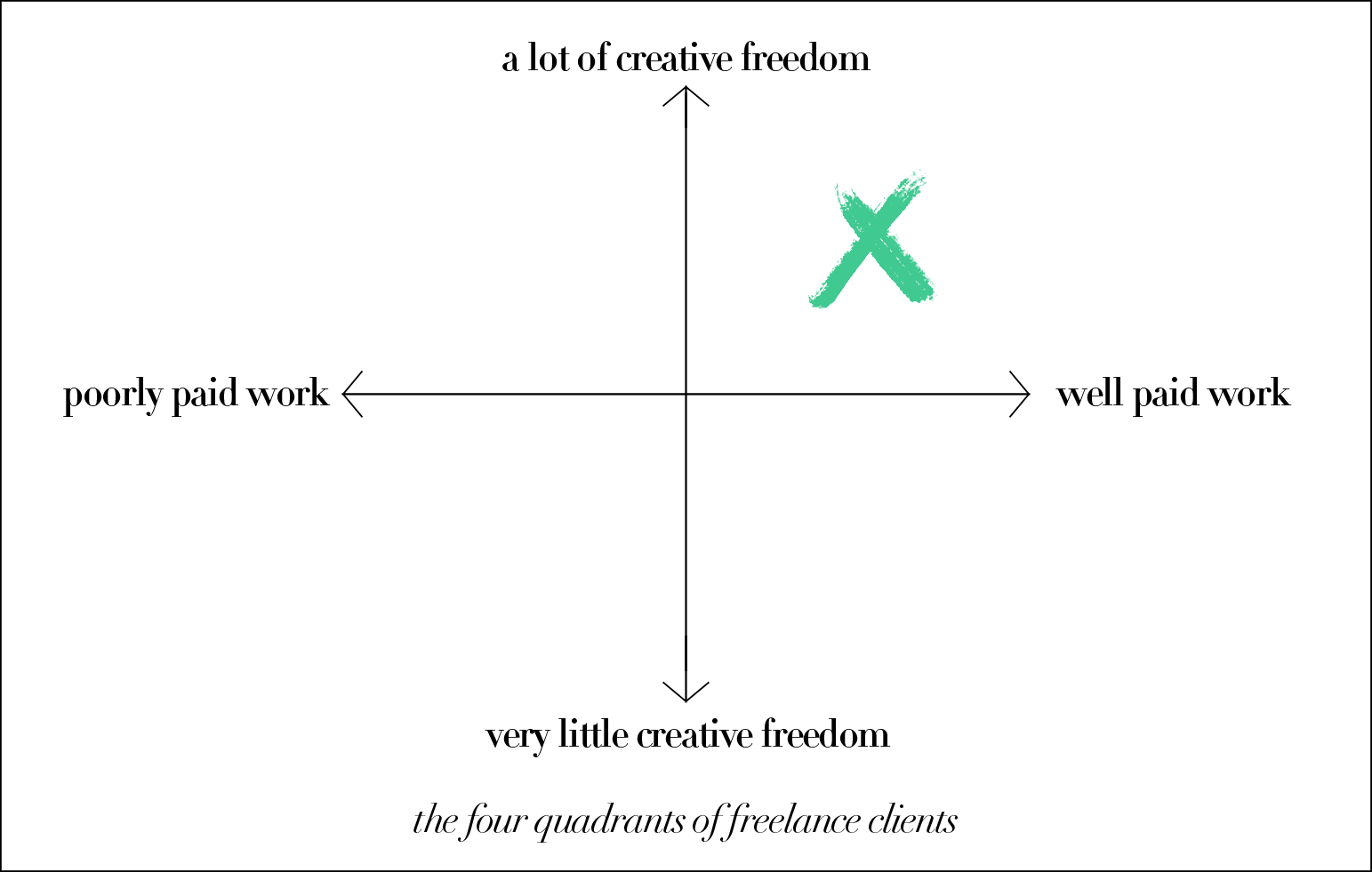

There are two categories of clients: those that pay poorly, and those that pay well. We can subdivide them into two more categories: those that give us a lot of creative freedom, and those that do not. Most of us start in the lower left quadrant, progress to the lower right quadrant… and then get stuck there:

In the bottom right quadrant are clients who hire us to create work in whatever style is currently trending. They hire us for our hands, not our ideas.

Where we want to end, though, is at the fat green X. The clients in that quadrant are the folks who want to hire us for our ideas.

To get into this quadrant, we need to gradually sell clients not only our hard skills, but our vision. But in order to sell our vision, we first need to find and develop it.

The reason many of us don’t reach this quadrant is because an original personal creative vision develops out of many completed personal projects, not just technical exercises.

Exercises are warm-ups: assignments from school that have us shading in spheres and doing value thumbnails. These exercises have their place—particularly when we need to master technique. But exercises are simple, one-dimensional, and quick. Projects, by contrast, are complex with lots of moving parts; they take longer and require more discipline to put together. It’s projects, not exercises, that an audience finally gets to enjoy:

We don’t read drafts, we read novels.

We don’t buy artist demos, we buy songs.

We don’t watch daily rushes, we watch films.

In the end, exercises are like the scaffolding for a building—necessary, but uninhabitable. At some point we need to build the actual house.

#everydays, #inktober and short, animated gifs are great exercises, but clients do not book us to practice—they book us to perform.

Our personal projects should be complete pieces that can stand on their own, and these pieces should fit together into a body of work: it is this body of work that convinces clients our art is worth paying attention to, that we’ve spent hundreds, thousands of hours thinking through our ideas and our outputs aren’t just flukes of inspiration but products of steady effort and experimentation.

Stop copying your peers.

Personal projects are ways to explore making something of our own, not further opportunities for us to copy the work of peers.

If all our peers are doing vector-based work, maybe it’s time to get into photography. If all our peers are doing flat, graphic designs, maybe it’s time to learn some perspective.

Personal projects are places we can develop our own interests, not follow those of others.

If you’re not into GIFs, you don’t have to build a personal project of ten GIFs because other better-known animators are doing it. If you want a break from the Wacom, you don’t have to paint a bunch of digital scenes. If you don’t like 3D, don’t learn it.

Find, instead, something you are curious about and willing to learn. These are paths that reveal themselves to you and no one else, and everything that grows on this path will be unique to you.

Copying others’ work is necessary in the beginning to build up technical skills, but to continue as a freelancer and artist in the long term we’ve got to stop looking sideways at others and find our own vision. The best clients—the ones everyone would kill to do work for—are after fresh, original work and they are willing to pay for it. This is the pocket we want to eventually play in.

The more we shape our personal projects around our personal interests, the more our projects will look and feel different to our peers, giving our work a better and better chance of being spotted by these clients.

Notice what’s original in your work.

There are clients willing to pay us for our creative vision, but first we need to know, intimately, what our vision is.

It takes time, experimentation and careful observation to figure out what our personal creative vision is—that is, what it is we have to say, and how we say it.

First we have to do away with ideas about being “successful artists” and humble ourselves by taking the small opportunities we see before us. These are usually tiny and unimpressive—maybe all we’re capable right now are small sketches of our hands and feet. Good enough. Start there.

And as we’re doing these small things, we notice when something excites us. The things that excite us are the seeds of something unique to us; they are seeds we found in the process of digging. Now we can cultivate and nurture them. We build a slightly more ambitious project around these seeds, and finish it. From that project, those seeds will push out of the earth and sprout some tiny leaves.

Little by little, we notice the seeds of our original thoughts, cultivate them, grow them, and eventually they will become our individual repertoire; repertoire that aren’t just copies of others’ work because we’ve watched them flourish from our own experiments and care.

Because our work is fresh, is original, we set trends instead of merely following them. We pull in desirable clients instead of pushing our work onto them. Our vision is disseminated widely from these client proejcts and other clients of similar calibre take notice and also want to work with us.

This is the positive cycle we all want to be in, and it all starts by noticing what is original in our work and drawing our own damn conclusions (pun intended).

Q&A.

I wrote and I teach a course on creative freelancing and have received many questions since I began. Here is a selection of some student questions and my best attempts at answers.

Should I wait until the economy picks back up to start freelancing?

No.

Start your freelance business now: this is a good time to re-organize your portfolio and work on new pieces. It’s a good time to revamp your website. It’s a good time to figure out where you want to go with your freelance career, and where you want to go with your creative work in general.

There is never a right time to start freelancing, and depending on the strength of your portfolio, it can take anywhere from three months to a year to really get your business off the ground and get consistent work.

Due to the pandemic, many opportunities will have disappeared but many new, unexpected ones will start to appear—and when they do, you want to be ready to take advantage of them. In short, don’t ever “sequence” the things you want to do. Just start doing them.

Once the economy does recover, all the freelancers who have been preparing in this down time will have a head start on the freelancers who don’t have a solid portfolio or pitch together by then.

Start right now.

Should I wait until I’ve skilled up technically before I start freelancing?

There definitely is a technical threshold you need to reach before you can support yourself by freelancing, and you can get a feeling for what that threshold is by checking out your local studio or agency websites.

Their work will give you an idea of what is at least an acceptable quality of work—the front pages of Behance tend to give you what the higher end work in your field looks like.

Your work needs to fall at or above your local agency’s quality level to begin with; this ensures you can get market-rate work instead of the paltry sums offered on UpWork or Freelancer.com.

Rule of thumb: if your work is not more technically proficient than what you see on UpWork, you should improve your work before you start freelancing.

However, waiting too long is also a common danger—technical skill is only partially the answer.

How do you manage to do epic work in your designer silo, and feel like your needs for community and connection are met?

It begins by being honest about what you really value.

If your personality favors deep connections with fewer people—maybe your work ought to flow and work with that direction rather than against it.

(Who is to say a life lived everyday in a studio making mugs is less exciting and meaningful than a career jetting from one meeting to the next?!)

Ultimately though, I think creative work is made to connect—if the work is rich and meaningful enough to you, it will be rich and meaningful to someone else. We should keep this in mind when we pursue our projects, because creative work can often be a lonely road.

“To begin with, drawing is a form of personal communication — but this does not mean that the artist should close himself off inside a bubble. His communication should be for those aesthetically, philosophically and geographically close to him, as well as for himself — but also for complete strangers. Drawing is a medium of communication for the great family we have not met, for the public and for the world.”

—Jean Giraud (Moebius)

I like your guidance around honing in on a direction, but I want to build my web site to promote a variety of services beyond design. How do I do that?

I recommend developing just one area of focus for your website to begin with.

This is to present your service with clarity to your potential client. A client who wants to do a motion design project is not interested in your other services. In fact, the more services you have, the more diluted your site starts to become—clients become unsure where your expertise lay.

It’s like if I’m considering buying a custom-built PC. I want to land on a site which is operated by a company specializing in custom-built PCs. I don’t want to see that the company also sells shoes and socks.

Specialized sites signal higher expertise in their area of focus. You want the client to perceive you as that expert. If you’ve got a number of interests and skills, you shouldn’t just advertise your various abilities by casting a wide net and hoping for the best.

That is what I term an “ineffective” generalist—one that is scattered and without focus. The “effective” generalist cultivates their many interests but then synthesizes these different areas into something singular, specific and useful to their target audience.

See my piece about generalists v specialists.

Is cold emailing “spammy”?

Don’t worry too much about whether potential clients consider your cold emails “spammy”. Worry instead that your email is genuine and tailored to the client you’re pitching.

Spam is something that feels generic and emailed to hundreds of people. If you customize each email to the person and the studio you are sending to (yes, this is a lot more work than sending a generic email to a list), you won’t come off as a spambot but as a real person offering their skills.

Remember, the potential clients you are emailing are used to receiving many, many pitches a day. Given this, your first job is to get their attention and get them to open the email. This might mean an unusual subject headline, which, once they open, reveals a thoughtfully designed email showcasing your work.

Don’t craft your message for the people who were never going to be receptive to it anyway—craft your message for the clients who will “get you”.

Some people do not like cold emails and won’t open your email, not respond to it, or have it as a matter of policy to only work with artists they already know. This is to be expected—this is going to be the majority of the people you email. But that’s okay, because they don’t matter.

What you do want is to catch the attention of the people who are open to working with new talent, who want to check out new artists’ portfolios, and you want to be memorable to them—when someone like that opens your email, you don’t want to have a plain, safe, generic email that doesn’t get them excited about your work (even though the email looks inoffensive and no one can say it looks “spammy”)—you want that person to smile a little at your daring little email dripping with sass and beautiful work and have them think hey, why not take a chance on her?

The Unconventional Freelancer Mentorship.

One of my personal projects for the past couple years has been the Unconventional Freelancer Mentorship.

Creative freelancing is difficult to get right. Not only do we need to focus on finding, pitching and doing paid client work, we’re also required to put in serious thought and effort into our personal creative work.

Creative freelancing is not widely taught, and what is taught usually boils down to generic tips like “go out and network! Get on every social platform! Make content…”

Unlike technical education where we’re learning a piece a software or specific techniques, the knowledge required to be a successful, long-term creative freelancer needs to be learned over time and tailored to each individual.

A graphic designer whose work has dried up after a decade of steady work is not dealing with the same problems as a recent art school grad with a weak portfolio.

An illustrator looking to transition out of a full time job and into full time freelance does not need the same help as an illustrator who has been freelancing for some time and now wants to increase the quality of his clients.

Unlike technical education, freelancing is a complex problem—you cannot come up with a solution in a series of five minute videos. How somebody should approach creative freelancing depends a lot on their personality, where they are in their career and what their aims are moving forward. No one-size-fits-all freelance course comes close to addressing any individual’s situation.

That’s why I run the Unconventional Mentorship, where I work with a small number of artists one on one, for twelve weeks. Students range from illustrators to graphic designers to animators and beyond.

With my Unconventional Freelancer course as the framework (more on that below), we will have an hour-long, 1:1 call every two weeks with personalized assignment critiques for all students in the cohort.

During our calls we will discuss individual challenges from building an online portfolio, finding a personal vision or developing a coherent body of work, as well as any struggles you’re encountering with your client or personal work.

There is no emphasis on using social media. This is not a mentorship about “how to use social media to achieve X”.

What I can offer is clarity on how you should move forward as a creative freelancer. What approaches you should consider in building your creative freelance business. There is a crazy amount of information out there for creatives wanting to freelance, and all of it is contradictory. Some say you should charge by value. Some say you need to over-invest in Instagram. Others say you should charge by the hour and network like crazy. There is no one-size-fits-all answer, but there is a right answer for you based on what you want to achieve with your craft.

We will discover and clarify that answer for you in our twelve weeks together.

It’ll be tough.

I won’t go easy on you, because this mentorship is a personal project of mine and I’m not doing it because I want to spawn an online education empire. I’m doing it because I’m in the trenches everyday as a creative freelancer and the more I share my process, the more I get to learn about it myself.

The Unconventional Mentorship is a twelve-week mentorship where we have an hour-long call every two weeks, with emails breaking down the contents of my freelancing system delivered straight to your inbox every few days. You’ll get my entire creative freelancing system delivered over twelve weeks in digestible pieces via email, and on our calls we will go over the assignments you submit, questions that crop up and we will strategize your next steps on the freelancing journey.

The button above will take you to more in-depth information about the mentorship.

Thank you for taking the time to read this guide and I hope you got a lot out of it. Pass it along to anyone else who might find this useful.

Be good,

Beini

The Unconventional Mentorship Testimonials:

“After many years of trying to scoop up any job I could, I felt my identity as a freelance illustrator stagnating. Working with Beini got me clear on my niche, got my story on point, and set me on an actionable plan. I started getting results in the middle of the course – working with better clients in more specific areas while furthering my own artistic growth. Thank you, Beini.”

“I’ve found the course and calls with Beini very helpful in moving forwards into a Motion Design career. She helped me focus how to communicate clearly to the types of clients I want to work for and also create an engaging portfolio site. Definitely the best business coach I’ve worked with who truly understands what it means to be a creative freelancer.”

“Beini’s course proved to be very useful in a time where I was going through a lot of self-doubt. She lays out a clear structure that guided me through the different steps needed to restructure my approach to freelancing while fine-tuning my craft. She encouraged me to experiment and look for unexpected ways to be more creative and find my unique voice. I found her feedback to be very thoughtful and thorough in every lesson. By the end, I had a solid understanding of the steps I needed to take, with a more defined direction of where I wanted to take my freelancing business.”