Starting from your current interests

I was asked to build the visuals for an interactive site with the Carnegie Corporation of New York – housing dozens of video, audio and written material concerning the historical, present and projected relations between the US and Russia. The site has since gone live.

Projects with a lot of creative freedom test the artist – given free range, what conceptual and technical direction do you take the work? It’s an opportunity to speak freely, so what the heck do we say?

To reduce the overwhelm, I started with my creative interests at the time. I was interested in exploring what I could achieve with inks and paints, following a class with Sterling Hundley who encouraged us to re-engage with physical mediums. It was a breath of fresh air after years of drawing, painting and animating on my computer.

(Ballpoint/monotype experiments)

Why start with our interests?

Because our mix of likes, dislikes, obsessions and repulsions is our individual path with “no charted ways and no shelter”¹; a path that leads us away from the lure of “collective conformity – a procedure which all the opinions, beliefs and ideals of [our] environment encourage.”² In short, our interests are the starting point for what differentiates our creative work from others.

If you’re here reading this, you’re interested in developing your creative voice, and that requires you to risk exposing to others the weird stuff you’re interested in. Don’t be shy.

Research and learning

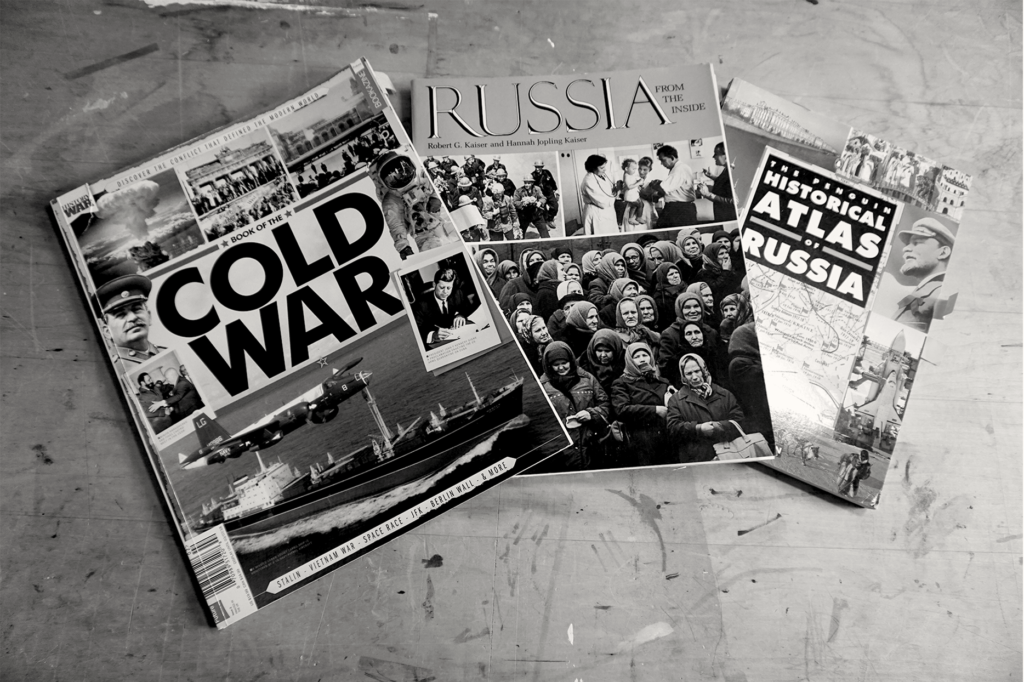

In keeping with this tactile, paper and ink direction, my first stop for project research was the Strand. If you’re ever in New York, visit the Strand. It’s four levels of new, used and rare books.

A bookstore or library is a great place to meander when you have a general idea of what you want to find and you’re open to material happened upon by chance. This takes time, subway tickets and a willingness to be inefficient. You can always drag a bunch of reference material off the internet and call it a day, but that gets boring fast and finding material that’s off the beaten path requires “variation, failure and serendipity.”³ In other words, finding interesting material requires you to waste time.

The books I found at the Strand were out of print, cheap and offered a ton of imagery nobody would bother putting on Pinterest but were useful in generating ideas for my project:

The next step in any project I take on is learning as much on the topic as I’m able. The more I’m able frontload my research and learning, the easier subsequent design ideas occur to me. It’s not always possible to learn the principles behind a new topic due to time constraints or industry jargon, but the deeper your learning the more likely you’ll draw parallels to other ideas that don’t seem similar on the surface⁴.

It also puts me in correct relationship to the material I’m dealing with: I can’t just slap Trendy Design Techniques on things I don’t understand and expect to end up with anything worthwhile. I try to look at each project as a chance to synthesize a new topic with my own tools and experience to create something original – or at least true to my interests and capabilities at the time.

Now it was time to put together stylistic directions for my client in the form of moodboards.

Moodboards

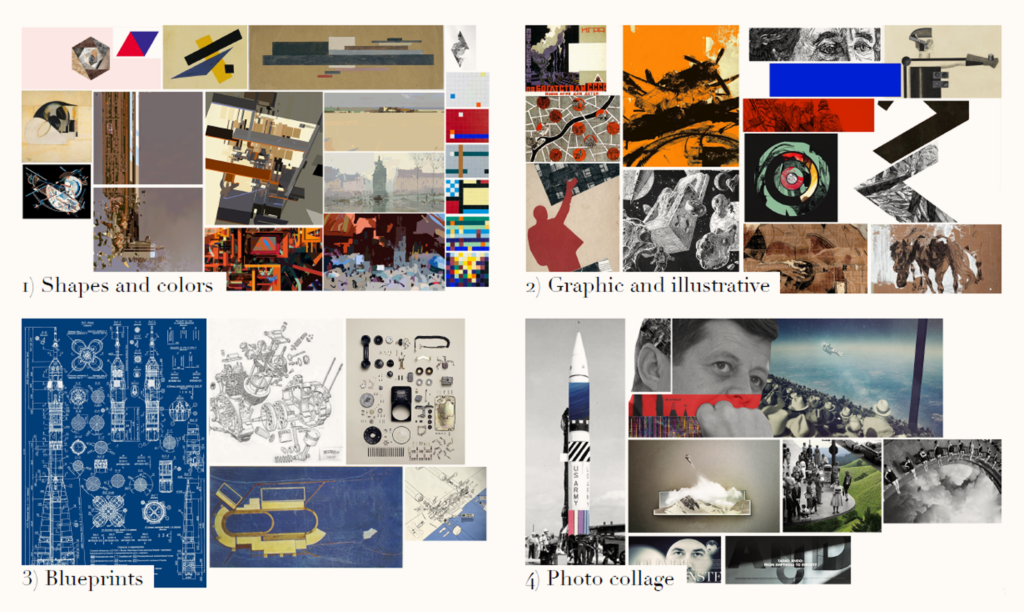

It’s a good idea to provide three (max four) stylistic options that differ from each other when presenting to a client. More than that and you burden your client with too much choice, and anyone with Netflix knows how that plays out.

Before hitting send, we look at the deliverables from the client’s perspective – is there a point to this style being here? Why is it relevant to this project? At this point I also consider technical limitations – if I’m the sole author I’ll need to know I have enough time and budget to execute the styles I’m proposing.

I put together four different moodboards based on my research and stylistic interests:

My fingers and toes were crossed for the illustrative option, but I made sure the alternatives were also appropriate and exciting. This has gotten more important the longer I freelance – as the overall volume of completed work increases, a focus on quality and originality keeps both client and personal work fresh. I challenge myself to come up with at least one aspect of whatever it is I’m offering clients that really excites me and would carry me through a project. This is especially true for projects that last more than a couple months.

Each of the moodboards was heavily informed by my interests at the time. Much of Sterling Hundley’s work peppered the Graphic and Illustrative moodboard, as did my hero Moebius and a few of my own ballpoint pieces. I try as much as possible to use client work as a tool to help push me further into my interests – this speeds along my artistic development and in turn imbues client work with fresh energy.

Client feedback

The client loved the illustrative direction and I got the green light.

I bought a set of Moleskines and dedicated one to the project. I wrote down what I wanted to accomplish with the project and what opportunities lay before me.

I wanted to immerse myself with the material at hand and allow the material to dictate how it wanted to be expressed. If you get quiet enough (meaning you put away the grand plans your ego has pre-planned and organized), you’ll start to hear what projects need from you – a brighter tone, maybe, more characters or more grit – instead of dictating how projects will turn out ahead of time.

Now I had a visual direction and a set of parameters for the project. I knew I wanted to use physical mediums and I knew the images had to be striking enough to hold the visitor’s attention and convince them to investigate further into the material.

Next I would experiment with inks and styles to come up with style frames.

1. Jung, C. G. (1989). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Vintage. pp. 344.

2. Ibid., pp. 343.

3. Hindo, Brian. (2007). “At 3M, A Struggle Between Efficiency And Creativity: How CEO George Buckley is managing the yin and yang of discipline and imagination.” Bloomberg BusinessWeek.

4. Epstein, D. (2019). Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World. Riverhead Books. pp. 107.